Michael Makembe is the king of Rwandan sampling. His work is an invitation to the unheard and the misrepresented. It is an exploration of sound textures and flavours. It is a journey of reviving the old and weaving it into the new. More than simply repurposing snippets of rural artists, Michael travels throughout the country to preciously archive the wealth of the Rwandan culture. He mingles and reuses portions of traditional singing in new recordings to pay homage to connect familiar sounds in new ways. Today, he builds a library of immersive audio experiences, called Sounds of Rwanda, to present the full spectrum of the country’s culture and genres from across the country from ikinimba, umushagiriro, imishayayo, igishakamba, to amashi.

“Cynthia, are you there?” Michael asked me on the phone.

I had just arrived at Nyabugogo Bus Terminus, but there was no sign of him. Because Nyabugogo serves as a crossroads for Musanze, Gisenyi, Kibuye, and Huye, I was not surprised to find myself surrounded by all of the inter-country coaches, minibuses, taxis, and bikes jostling for space. This is Rwanda, after all. You never know what might happen. This place might get a facelift in no time. The masterplan is still a long way from completion, and it continues to surprise us. Construction has already begun in the area to create a more spacious infrastructure as well as more bus terminals to reduce the number of passengers queuing in Nyabugogo.

Michael called me again.

“Is it inside the compound that you are? Do you mind stepping outside? I am there at the Kobil Petrol Station. It will be easy to locate each other.”

Despite the fact that the outside of the Nyabugogo Bus station was as crowded as the inside, I immediately recognised Michael. We could carpool instead because he had located a car on the streets.

"Uri kunyumva, Emmy? We should get to Gisenyi by midday," Michael said as he stuffed his many bags full of recording gear into the car's compartment with his phone wedged between his ear and shoulder.

As soon as the car was full, it took off. The scenery abruptly changed from Nyabugogo's congested traffic to a typical Rwandan rural countryside with stunning undulating hills and valleys.

“So tell me...” I asked Michael as we made a stop-over at Nyirangarama for sambusas. “What prompted your desire to become so immersed in the culture in the first place?”

Though I don’t have any experience in recording and music production, I have a broad interest in Rwanda's creative landscape. And I knew the trip would inspire me, particularly in terms of how to draw this portrait of him, which I enjoy doing on Rwandan creatives. The longer I stay in Rwanda, the more I realise how abundant Rwanda is in creativity, resources, and ideas, all of which serve as sources of inspiration and nourishment. As a result, a new generation of Rwandan artists is blending culture into their work, resulting in art that is rich in tradition, modernism, history, and beauty.

“You know Cynthia, all I have ever wanted was to get in touch with my roots and my culture,” Michael responded. ”As I have spent so many years outside Rwanda, I had to take the time to find this identity in me. It is something that once you lose, it takes time for it to come back. As such, tradition never comes to you. It is you that need to come to your roots. It has to come from you.”

Michael's story is one of unshakeable faith and perseverance in the face of adversity. His mother had sent him and his older brother to an English boarding school in Uganda when he was eight years old. Michael began to develop an interest in playing the guitar as soon as he landed in Uganda. Self-taught, his talent quickly blossomed and matured to the point where the school director saw him as a valuable asset and decided to form a music band with him as the leader. As a result of his exposure, Michael was able to be transferred from his Ugandan school to a Kenyan school for a few months. He then got transferred back to Uganda for a couple of months and then eventually to Nyundo Music School in Rwanda to finish the remaining three years he needed to complete to graduate from high school.

The pivotal moment occurred while working with the Kigali Up festival, which was founded by Nyundo Music School's director. He had the opportunity to do sound checks for artists and perform as a backup singer as a student at the institution. As a result, he met Ismael Lô in 2018 and performed one of his songs for him, Tajabone (1992), which is the tune that launched Ismael Lô's international career. As a self-taught multi-instrumentalist, Michael accompanied himself while singing using a harmonica attached to his guitar so he could play the guitar while singing. Ismael Lô sang with him in tears and later invited him to open for him at festivals in Senegal. When Michael returned to Kigali, he began to be invited to prominent events to perform and met artists such as Youssou N'Dour and Baloji. Then, in 2020, Saul Williams, an American singer, songwriter, poet, and actor, approached Michael about scoring the soundtrack for his film Neptune Frost, which was shot in Rwanda. This project inspired Michael to continue advancing in the beat-making world, despite how niche it is. His goal is to put Rwanda on the map and to make its rich legacy recognized through contemporary music that young people can relate to. In the meantime, he's working on a library of immersive audio experiences called Sounds of Rwanda, to present the full spectrum of Rwanda’s culture and genres from across the country from ikinimba, umushagiriro, imishayayo, igishakamba, to amashi.

As we approached the mosque, the driver announced, “Tugeze i Gisenyi.” Michael replied, “Our motel is close by. If you don't mind, we'd appreciate it if you could drop us off there instead.”

Michael would get into this kind of journey every time he wanted to capture rural artists upcountry because he couldn't always get rural communities to his proofsound facility in Kibagabaga. Despite the fact that recording such a performance takes only 2 to 3 hours, we arrived a day early so Michael could pitch the concept in person and establish confidence. Hence that time had to be factored in and we needed to spend one night at a motel.

We had to rush back outside after dropping our bags in our rooms to pick up Michael's friend Emmy, who hails from a family of poets and artists. The two had met at the Ubuhanzi Annual Art Talent Competition two years prior. Michael wanted him to introduce us to his great-uncle Nina Gakwisi Rudaharana.

We gathered Emmy and his great-uncle Nina at Ibere rya Bigogwe (Breast of Bigogwe). Despite the fact that the rock does not resemble a boob, it is a useful landmark for orienting yourself.

“It's such a privilege for me to finally meet you Nina,” Michael exclaimed happily. “Numvise amakuru menshi akwerekeye.”

Nina was there, dressed to the nines in his suit, mask, trilby hat, and walking cane, which he also uses to herd his cows. Nina is noted for being the leader of a traditional dance troupe that specialises in the Ikinyemera form of dance. When you google ikinyemera, the first thing that comes up is Nina's face. Michael was looking forward to witnessing Nina's troupe perform and adding these new recordings to his repertoire because he had never captured the ikinyemera dance style before.

With him, we walked down the street. The main road in Bigogwe was packed, with multiple shops and pubs all painted in MTN or Primus trademark colours.

“Nina, this is my friend Cynthia who is going to take pictures.” “I was going to say that you are not making introductions,” said Nina jokingly. “Afite inseko nziza”.

Obviously, I always feel a little dumb when people in front of me are talking about me to see how much Kinyarwanda I know. Though I was exposed to Rwandan culture throughout my childhood in Switzerland, acquiring the language has always been a challenge. Naturally, not knowing the language fluently prevents you from grasping the philosophical richness and the profound significance of Rwandan heritage. Nonetheless, Michael did an excellent job of normalising the situation and putting everyone at ease, despite the fact that my presence was quite imposing as I was there with my camera trying to capture every bit.

“Nta kantu wamuririmbira? Even something brief?”

“Well, I'm not sure what I can sing." Nina said, his face solemn.

“One day, I entered a competition in which we had to sing about how rural women were marginalised," Nina continued. "As I considered the imposed issue, I realised that if I said that rural women were left behind, I would be admitting that my own wife had been left out as well." As a result, I came to the conclusion that rural women are not marginalised, but rather cherished members of society. As a result, I decided to alter the brief slightly.”

Nina cleared his throat and started singing:

“Umugore wo mu cyaro yemera imirimo,

Yiyemeza guhinga agatunga urugo,

N’uwo mu mujyi rwose ntamurusha ibigwi,

Umwe atwara ikaramu undi agatwara isuka,

Ibyo byose ugasanga bikomeje urugo,

Naritegereje nsanga abagore ari bamwe.”

(The rural woman is a hard worker.

She commits herself to cultivating to feed her family.

Even the urban woman doesn’t outshine her.

One takes a pen, while the other takes a hoe.

And both tools ultimately make them meet the needs of their homes.

I have observed them and found out that both women are the same.)

“We are good to go,” said Michael as he was meticulously checking inside all of his bags if he had brought each piece of his equipment.

We had gotten up quite early to return to Nina's house, as he had requested that we be early in order to drink milk before the performance.

“When someone comes to your house in Rwandan tradition,” Nina explained, “you have to give them milk. It's a pity to receive such distinguished visitors and not give them a particular treat.”

Michael rubbed his hair with a coil sponge to get his signature defined curls, then crouched down to tie his shoelaces, slipped the wide legs of his jumpsuit over his Yeezys, and zipped his garment all the way up before heading to the car. His alter ego had been triggered. Michael had constructed a distinct image of himself from head to toe that allowed him to take on this flamboyant persona.

I moved to the front of the car as we got to it so that I could snap better shots. As I sat there, it occurred to me that I didn't have enough cash on me to pay my share of the troupe's remuneration.

"Wouldn't it be easier if I sent you the money through MOMO right now, so Nina gets it all at once?" Paying the troupe separately appears to be a bit of a hassle.

Michael smiled and nodded. I opened the Nokanda app on my phone, picked Michael from my contacts, and sent the money. When I received the confirmation message, though, an unknown name displayed as the receiver on my screen.

“Wait... Am I sending the money to the right number? Why is the message reading Ishimwe Michel?”

“Because it is my actual name!” laughed Michael.

I couldn’t picture him with another name. It suited him so well.

“How did you come up with Michael Makembe?”

“Well, I started getting myself called Michael and not Michel when I moved to Kampala. People there were not used to hearing Michel as a male name. And so, it was just easier getting myself called Michael by anglophones. And Makembe is from Icyembe. It is one of my favourite instruments. Though the plural of Icyembe in Kinyarwanda is still Icyembe, it is actually Amakembe in Kirundi. It sounded so nice. So I decided to make it my stage name.”

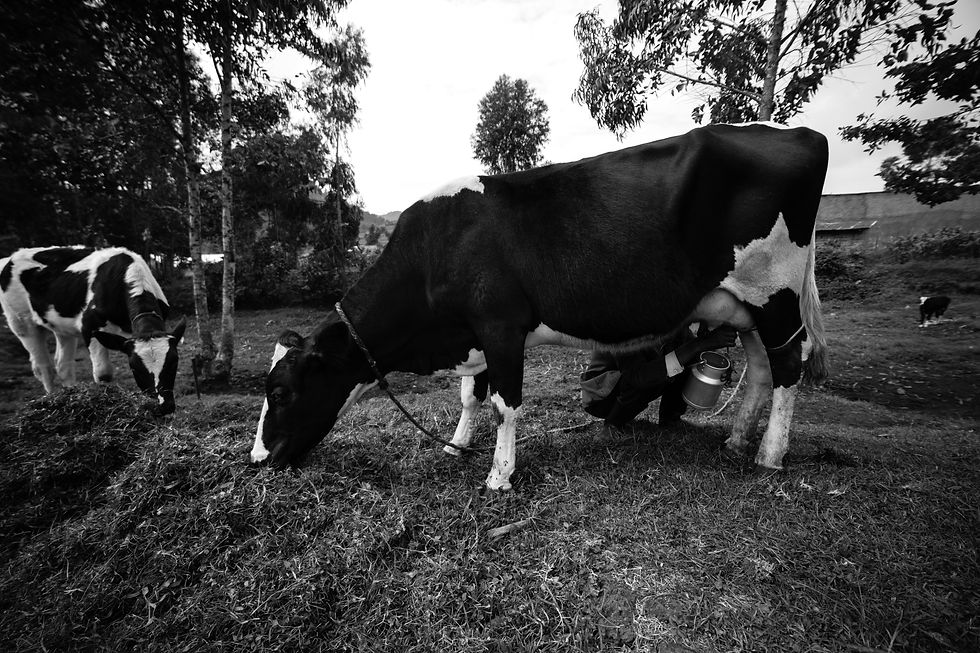

When we reached Bigogwe, Nina welcomed Michael, Emmy that we had picked on the way and I to his house with a steel milk churn in his hand. He then knelt next to the cow and began squeezing the teat.

“Nina,” interrupted Michael, “aren't you supposed to be singing while milking the cow? ”

“Step aside. You guys are scaring my cow! ”

“Aren’t you supposed to be singing while milking the cow?”, insisted Michael while stepping back.

“Not really,” replied Nina, still focusing on the milking,” except when I praise the cow.”

“Can you do that, please?”

“I already did,” replied Nina curtly, ”and the cow heard me.”

Nina finished milking his cow and filled the churn to the brim, and handed them to us.

“Come on, drink quickly”, said Nina, smiling at us with satisfaction as we honoured the culture. “Igihe cyo kugenda cyageze!”

His friends Rwoganyanja, Rwagasore, and Byiringiro had arrived at Nina's house to take us to the location where they planned to perform because the performance couldn't be held in Nina's yard. They were all dressed in suits and cowboy hats, with a bamboo walking cane in one hand, just like Nina.

“On y va!” would suddenly tell me Rwoganyanja in French. He had been part of a Christian choir singing in Latin and in French. He was enjoying practising French with me. From time to time he would say “Attention!”, “Sautez!”, “Marchez!”.

We ran upon farmers who had picked potatoes and were on their way to a truck to sell their sacks of potatoes as we hiked up the trail. As we approached the Gishwati Forest, the environment became increasingly green. The meadows were so lush; the bright green grass, the rounded curves of the hills, along with the few black and white cows that look like the Milka cows from the chocolate packaging – Inka z'Abagogwe, as we call them – remind me of the Gruyère region in central Switzerland. On the other hand, the Karisimbi Volcano, the tallest of the Virunga chain's eight volcanoes, was gradually looming behind the houses along the main street. I never anticipated the volcano would be visible from where we were standing. Even from afar, it looked very imposing.

Michael began opening his bags and removing all of his equipment as soon as we arrived at our destination. I was given some stands, microphones, and recording equipment, all of which had a plethora of buttons that I had no idea what they were for. I had underestimated the amount of planning that going out into the field to record performers necessitates.

“Amahoro y’Imana abane namwe!” Michael extended a warm welcome to the group. Nina, Rwoganyanja, Rwagasore, and Byiringiro were joined by other dancers for the performance.

Michael turned to the assembly and said: "I am the one who summoned you to this location. It's an honour for me to be able to speak in front of individuals who are so much wiser than myself. I've come to learn from you, and I'd like to share what I've learned with you. When I was eight years old, I moved to Uganda to finish my education. I studied foreign music as part of my studies. I've made it my aim to focus on my country's unique cultural legacy since I returned as a young adult."

“Urakoze !” Nina responded in a solemn tone. “Gusigasira umuco wacu nibyo twifuza. You see these young people; they were not born knowing how to dance. It’s thanks to education and willingness. The same way you want to learn about music, the same way they want to learn about their culture. So we train them. And we will do it for you too.”

All of our preparations for this performance were now paying off in front of our eyes. The troupe began dancing Ikinyemera using the routines and tunes. To resemble the long horns of the cows, they kept their hands aloft throughout the dance. The singing was a lead vocal with captivating vocal textures entwined with beautiful harmonies sung by the choir and rhythmic hand clapping. Everything is sung a cappella.

Michael knelt down and covered his emotional eyes with his hands. It was truly a magnificent and touching spectacle. And all of this was part of Michael’s creative process for him to create art. I was very humble by this experience but also very honoured to be able to witness it and to see how the cultural heritage of Rwanda is a source of inspiration for these artists. I have experienced first-hand how they find meaning in the unexplored and the overlooked of Rwandan culture in order to propose new forms of art. There really is a revival in Rwanda; you have to be there to see it.

Comentarios